Le Beau Serge in New York

Claude Chabrol 1959, sur la plage de la Nouvelle Vague

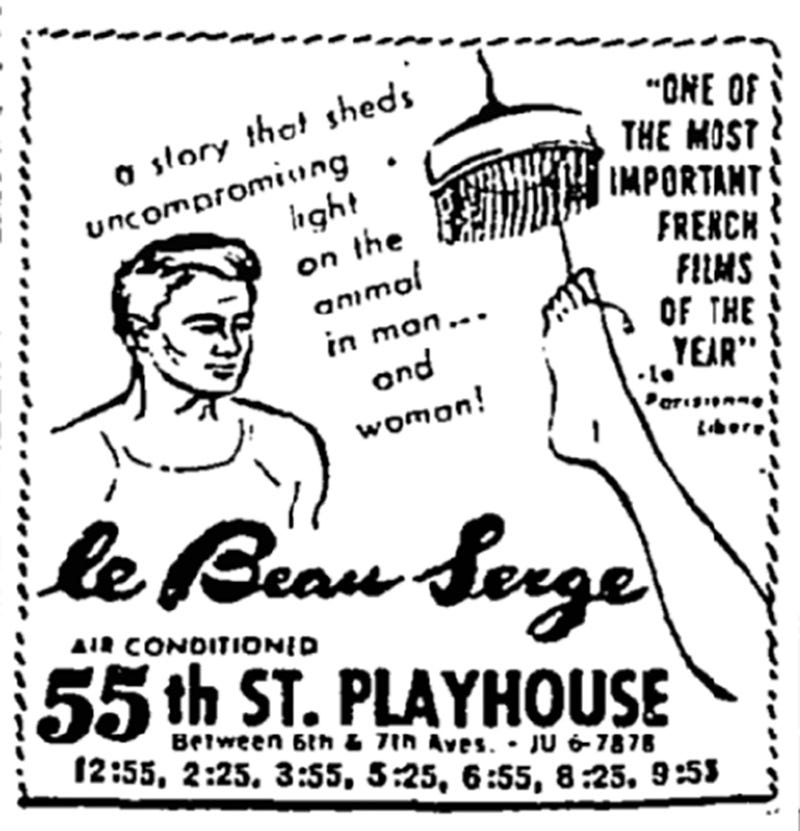

The first of the films known as French New Wave arrived in New York in August of 1959. Twenty-seven year old Claude Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge opened at the 55th Street Playhouse, a 300 seat repertory cinema that offered foreign films, and, later, Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys. Further downtown, Chabrol’s Les Cousins opened in November of ‘59, following Truffaut’s The 400 Blows at The Beekman. At the New York Times, Vincent Canby hailed Truffaut’s film as a masterpiece, but Chabrol’s summer debut was relegated to Abe (aka “Doc”) Weiler for review.

“They offer no solutions in their somewhat diffuse drama. A clouded but often disturbing picture of French youth.” Weiler had little encouragement for the new wave of “angry young men” directors, preferring a noir “full of sound and fury, murder, sacred and profane love and a fair quota of intramural intrigue” like Fritz Lang’s While the City Sleeps, “more flamboyant than probable, a tight and sophisticated script.” It’s difficult to imagine him finding anything diverting about Jean Seberg washing her feet in the sink.

Mr. Weiler, perhaps too pressed for time for an Alliance Française class, believed directeur de production in the film credits meant Jean Cotet, “whose name, like those of the other principals, is new to America moviegoers” was the film’s director. Regarding Un film produit écrit and réalisé par Claude Chabrol, he allowed the credit of “writer-producer.”

The boys made the revolution on le sou de grand-mère

James Monaco says Chabrol often doesn’t get the credit he deserves. For example, David Thomson calls him “a fringe instigator of the original New Wave,” as though he were Pete Best. In fact, without Chabrol, the first surge of directors may not have gained their moment. “For the first few years of the New Wave, Claude Chabrol was its financial angel,” says Monaco. Mais bien sûr Monaco means Agnès Marie-Madeleine Goute was the financial angel. When Agnès Goute inherited money from her grandmother, Chabrol brought a “practical intelligence to the financing of the early New Wave films.” He created a film production company, AJYM, named for Agnès, and their sons Jean-Yves and Matthieu. Chabrol first produced Jacques Rivette’s Coup de berger, then his own Le Beau Serge and Les Cousins.

Bragging rights: Truffaut, Godard, and Rohmer had made short films using 16mm. Rivette’s Coup was shot on 35mm making it the first professional film of the New Wave.

Cherchez la femme 👀

Bear in mind, Francois Truffaut’s first wife was Madeline Morganstern, daughter of producer Ignace Morgenstern, owner of distribution company Cocinor. It was a mutually beneficial relationship. Cocinor was up against powerful, well-financed distributors Gaumont and Pathé. To compete, Morganstern virtually cornered the New Wave market he and Truffaut helped to create, distributing Truffaut’s Palm D’or winning The 400 Blows, Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour, Godard’s Contempt, Buñuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid, and Vadim's And God Created Woman, among others.

Meanwhile back at The Gray Lady

Weiler was quite a character. He thought it was snooty when the New York Times gathered the arts writers as a culture desk under Joseph Herzberg. Weiler turned down his boss’s request for a meeting telling the senior editor, “Sorry, Joe, I’m busy painting a fresco.” Apparently he was offended by the idea movies were culture. It might mean he’d have to learn a little French.

The man bringing art films to New York, Irvin Shapiro (Weiler calls him “Irwin”) had gotten his start in the city working briefly in RKO theaters and the Little Carnegie, venues that often showed art house movies. Shapiro quickly grasped the opportunity for a distribution business and formed Films Around the World to cultivate the “new moviegoing public that just wants quality and not stars or producers’ labels.” The access and centralization Shapiro provided helped small theaters create an identity as specializing in repertory, foreign and art house rather than feature these films in a mix with current American cinema.

Weiler covered Shapiro’s import of Le Beau Serge and its twin feature, The Cousins in his Times Local Screen column. “Mr. Shapiro is not convinced that, having been made by members of the “new wave,” (Chabrol’s The Cousins) is a fresh, qualitative work.” Much as he wanted the Times’s coverage of his films, Shapiro was duly wary of Weiler’s penchant for “close enough” detail, and sidestepped politely. “I don’t know how to define quality,” he said. Satisfied with his scoop, Weiler did Shapiro the favor of touting another of “Chabrol’s films”, Out of Breath.

Informers inform, burglars burgle, murderers murder, lovers love

Chabrol was credited as technical advisor on Breathless. In fact, he was attached to the film only to provide producer Georges de Beauregard with a provisional sense of financial security the film would actually get made and be credible.

While Jean-Luc Godard was working as press attaché for 20th Century Fox in France, Fox was distributing de Beauregard. Godard, true to his pugnacious reputation, told him,"your film is shit." (Godard and Weiler had similarly subtle assays.) Rather than slapping him in the head, Beauregard cannily challenged Godard to do something himself. Beauregard gave him the script for a film he was then producing, Schoendoerffer’s Island Fisherman. (Schoendoerffer went on to write Pêcheur d’Islande with the seasoned André Tabet.)

Chabrol said, "Godard may not admit he worked- or pretended to- on that script for six weeks until he persuaded de Beauregard it would be better to make the Poiccard film." Thanks to Granny, the angry young men had their chance. Chabrol himself went on to make over fifty feature films. He made light of throwing his weight behind Godard at the critical moment. “We were convinced we were all geniuses.”