Sunday Coffee

Deleted scenes from this week's column, "History of a Memory"

While writing History of a Memory, new ideas kept crowding the page. Words have their cousins, replica/ replicant, which call up their own echoes: reply/ replay. I kept circling how projection works in film and in life: how we project ourselves onto others, how we present ourselves outward, how memory itself spools like a private cinema, unpredictable as a kaleidoscope and not always a welcome intrusion.

The edit

One idea I couldn’t fit kept returning. In Blade Runner 2049, questions of artifice aren’t only part of K’s work environment. The issue of what it is to be real follows him home to dilemmas of desire and connection. K’s holograph girlfriend Joi devises a way to cross into his physical world. She overlays herself on the doxie Mariette, syncing her gestures to Mariette’s body so she can touch him. The attempt is tender, but always a little off, two presences flickering in and out of alignment.

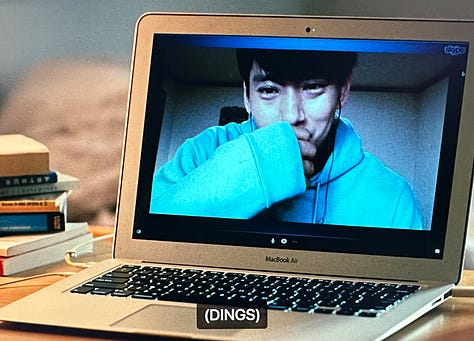

In Past Lives, when Nora calls Hae Sung on Skype, the familiar tune plays. Including that iconic set of beeps and tones is a canny choice Celine Song makes, summoning instant nostalgia and yearning. (Online, people have commented the Skype tones make them suddenly homesick; for me they still carry the tiny twinge something special is about to happen.) Then Hae Sung’s face appears, jittering in the small laptop window.

Technology is a specious present

As I watched this scene, I thought of Joi and Mariette. The sync imperfect, frames of the video drop out in space, and the image stutter itself is like memory. I imagined that Nora at her desk in New York was seeing not only Hae Sung in Seoul but also Na Young at twelve, both layered into the same fragile frame.

I replayed the scene more than once, trying to understand how it works, why it stuck with me. Perhaps because it rhymes with lived experience, a la William James: feeling the present and its vanishing at one time in the faint shimmer of what cannot be held still.